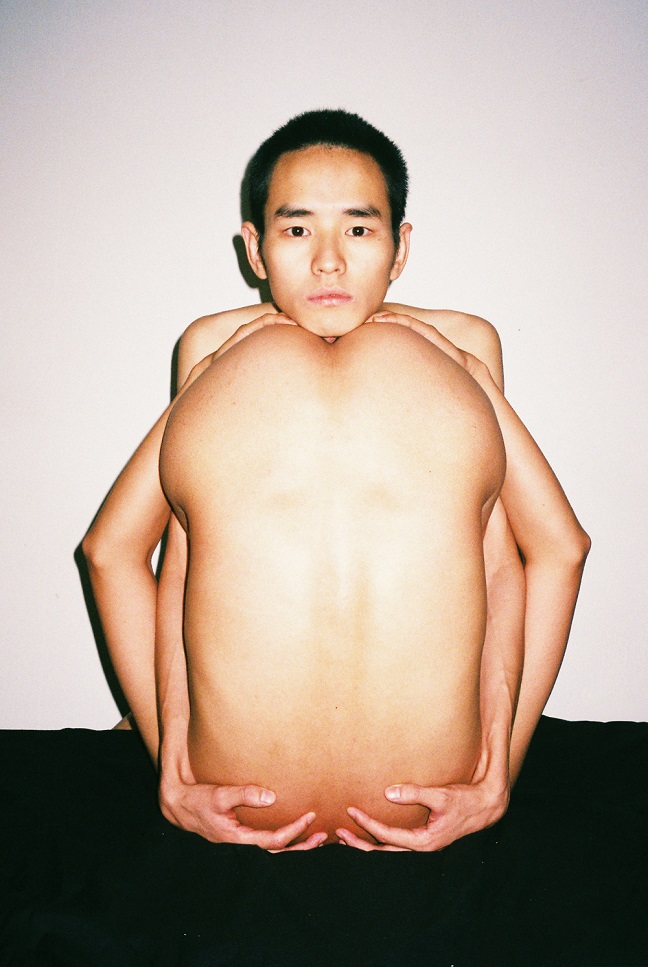

30 March 1987 – 24 February 2017

“People come into this world naked and I consider naked bodies to be people’s original, authentic look.”

Over a month ago photography lost one of the leading figures of a new generation of Chinese photographers, Ren Hang. This was at the time in which he would have been working towards a major solo exhibition at Foam, Amsterdam. When looking at photographs that can only be described as visual poetry, it is more important than ever to consider the future of Chinese art and culture.

Ren Hang moved to Beijing when he was 17 to study advertising, and after picking up a cheap point-and-shoot, and taking nude images of his friends simply to “relieve boredom”, he gained a huge online following leading to international shows and widespread success.

Hang never wanted to be the spokesman for his generation, though that doesn’t mean much: anybody who did would never have become one. It’s not a role he campaigned for, rather it was urged upon him. It was his daring and bold images which originally seized the western hemispheres’ attention, that labelled him a political activist.

Unjustifiably, similar to his creative contemporary Ai Weiwei, Hang was threatened and incarcerated on several occasions. However, Hang maintained that his pictures have nothing to do with politics. “It’s Chinese politics that wants to interfere with my art.” Through intertwining nudity with nature and making edenic connections with structural, bodily forms— Hang demands an acceptance of the nude as norm, a controversial and illicit standpoint in the People’s Republic of China, where pornography has been illegal since 1949.

People looked to Ren Hang as a luminary because his images battled with our imagination, in the end surprising us with something beautifully simple. It is the inescapable context in which they were created that forces them to be bi-literate. Hang courageously pioneered a counter-culture, forging an awareness of the potential for radical cultural change, which would become the social matrix of a sexual revolution in the face of an opposed government. His work also reminds all of us of the progress still to be made in our own surroundings, where freedom of expression and movement are abundantly lacking. It is a message to us all, that individual acts have far reaching potential and ultimately is a testament to Ren Hang’s attribution as a extremely talented and sorely missed artist.

We hope his work remains at the forefront as an example so that he continues to inspire people to celebrate natural essence against deeply complicated constitutional relationships; artists and progressives still have a lot to learn from Ren Hang.